A chunk of thick, nineteenth-century beer bottle repurposed–right edge retouched–as if it were a flint flake.

A chunk of thick, nineteenth-century beer bottle repurposed–right edge retouched–as if it were a flint flake.

Lightning-struck.

Burned to the stones, then scoured flush by weather and time.

A tiny–1.7 cm–obsidian point, probably Ancestral Puebloan.

Flint from a flintlock–Navajo, at a guess. The flint itself is probably from the Brandon flint mines in England, knapped there and imported as a finished product.

Remains of a WWII dummy bomb. The brightly-colored sands and clays of the desert were exploited as targets.

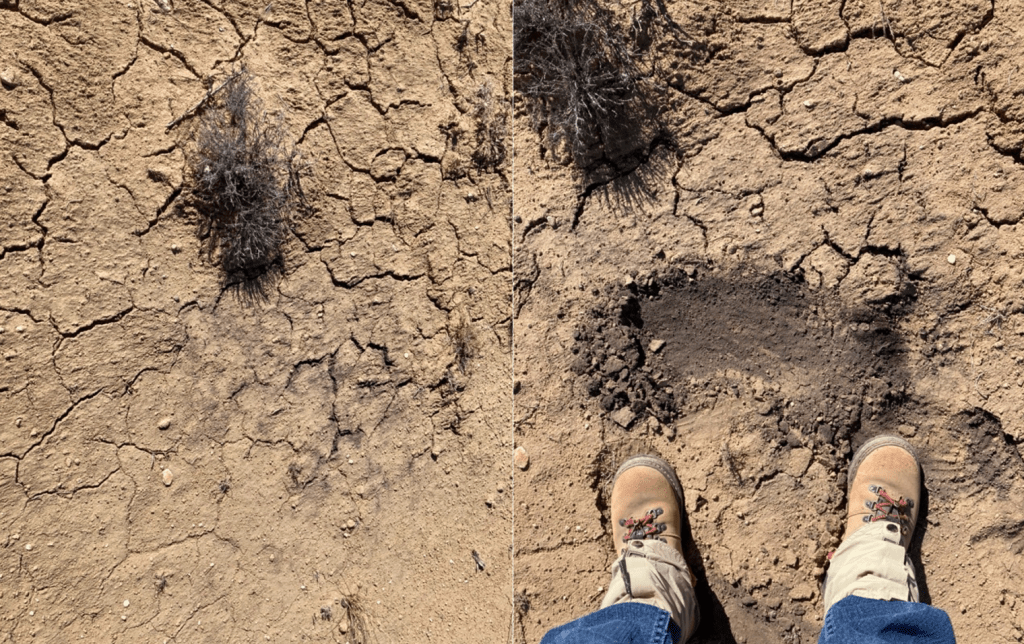

Two weeks ago we walked on dust. But a few days of snow and rain have swollen the bentonite clay in the Morrison Formation into a soft, brickled carpet. Sun and wind will soon turn it to dust again, except where cryptobiotic organisms can anchor it.

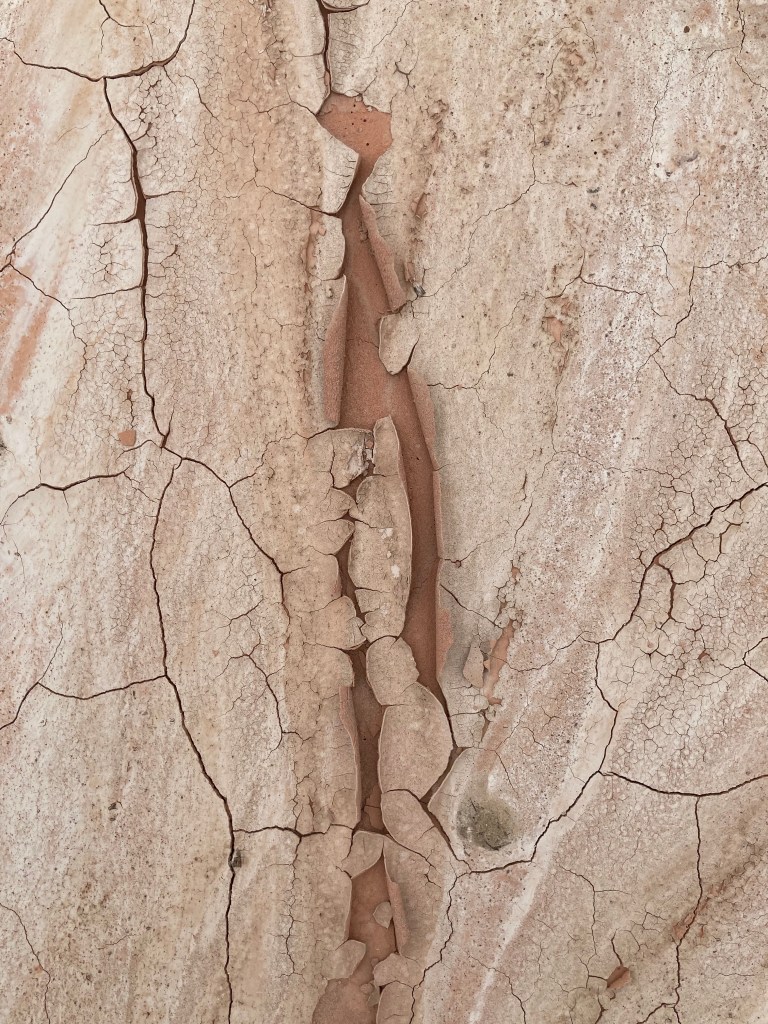

In another stratum of the Morrison, the winter wet had brought down a layer of outwash like melted creamsicle: flat as a dance floor, delicate and thin as old wallpaper.

The square-cornered foundation and a couple of scattered sherds say Ancestral Pueblo, but both the vertical orientation and the size of the stones are unusual and impressive. Walls and roof–jacal style, the Southwest version of wattle-and-daub–have long since dissolved into the desert clay.

And another house. I have no idea whose, but the excavator left their claw marks above the doorway.

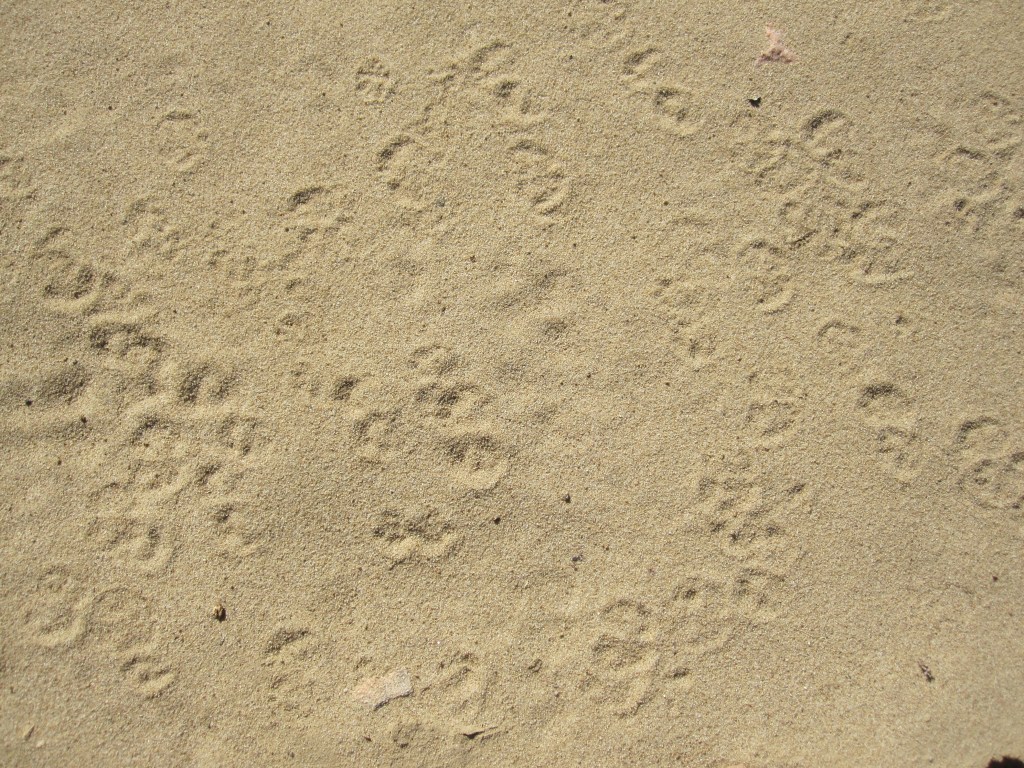

Mouse? Packrat?

I vote for a jumping rodent. See how the footprints are clustered? Maybe a kangaroo rat? The soil is clay. It was sloppy mud a couple of weeks ago, now hard as ceramic. This dance should last until the next good rain.

We threaded the wind- and rain-scoured mesa rims among scattered flakes and potsherds of millennia. Here and there, a firepit so old that its ashes were only a faint stain in the dun soil.

The next wind and rain will hide it again. But the metate was in plain sight, the only flat surface among boulders. The last pecking to renew its grinding surface had become dark spots, and the worn surface on the left side was a smooth bowl under the hand.

In the muddy pool of an elk footprint, frost at work.

About seven thousand years ago, a culture that the invaders of five hundred years ago called the Bajada were making tools out of basalt.

Basalt. Were they crazy? Gluttons for punishment? Basalt is hard, grainy, homely, and close to impossible to knap. But by god it’s tough. It takes a lot to break it. Maybe that was the attraction?

We have to assume that the so-called Bajada–we have no idea what they called themselves, though they were all over the Southwest–were tough. And that hunters found a reason for their choice of that difficult material.

Where you find those basalt flakes you may also find the metate where gatherers ground wild grain:

Their camp is eroding into the arroyo. But if you’re alert you can spot what’s left of the place where folks sat around knapping basalt, sharing chapatis made of wild grains, and telling stories about the next seven thousand years.

On the slope below a line of rubble that might–or, in that stony country, might not–have been a tiny ruin, was a cascade of the coarse grayware of the Late Archaic.

At first glance it seemed like a “pot drop”: the in situ remains of one vessel. But if you look closely you can see that the corrugation was done by a couple of different hands.

Not far away there was a little dance floor: