A nineteenth-century Hispanic homestead, long abandoned in its broadcast midden of rusty metal and purple glass. Axe-cut and adze-hewn beams, windows and doors trimmed with dimension lumber.

It was the first day cool enough, morning only, to scramble and side-hill in the mesa’s shadow. By noon the pale Cretaceous clay was too hot for pleasure.

11,000 feet. The lowlands won’t see asters for another month.

South from the Sandia Crest trail. Summer rain.

A chunk of thick, nineteenth-century beer bottle repurposed–right edge retouched–as if it were a flint flake.

Lightning-struck.

Burned to the stones, then scoured flush by weather and time.

The leg it slashed –clinic visit, tetanus booster–was mine.

Vote to control shooters on public lands.

A tiny–1.7 cm–obsidian point, probably Ancestral Puebloan.

Flint from a flintlock–Navajo, at a guess. The flint itself is probably from the Brandon flint mines in England, knapped there and imported as a finished product.

Remains of a WWII dummy bomb. The brightly-colored sands and clays of the desert were exploited as targets.

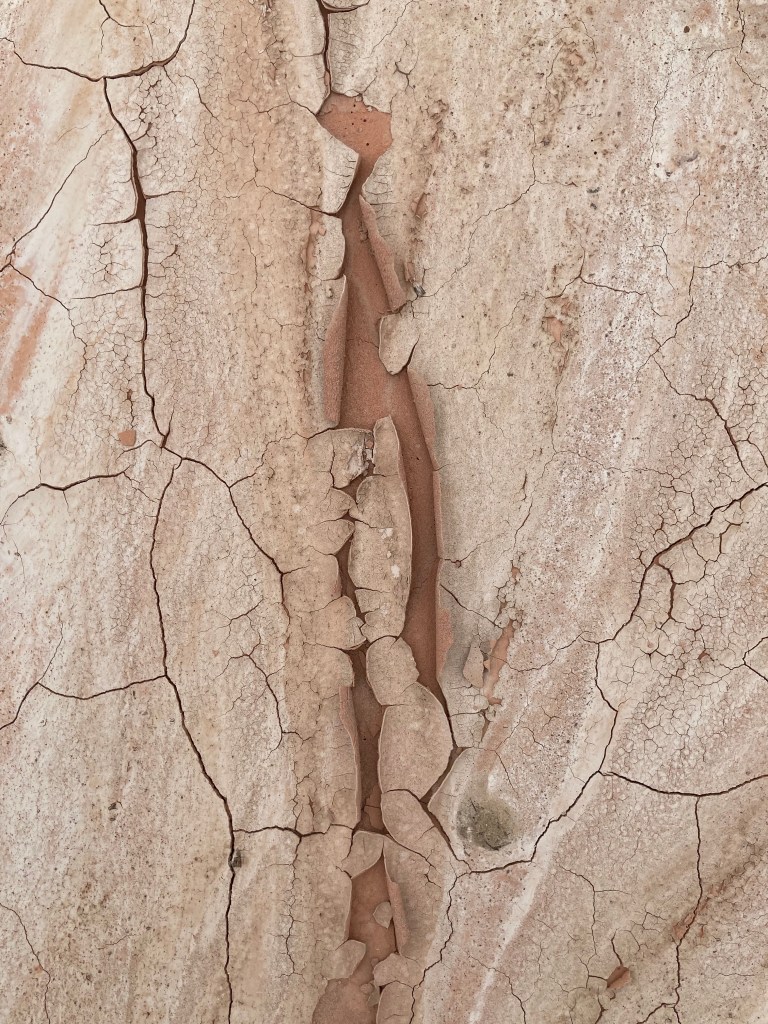

Two weeks ago we walked on dust. But a few days of snow and rain have swollen the bentonite clay in the Morrison Formation into a soft, brickled carpet. Sun and wind will soon turn it to dust again, except where cryptobiotic organisms can anchor it.

In another stratum of the Morrison, the winter wet had brought down a layer of outwash like melted creamsicle: flat as a dance floor, delicate and thin as old wallpaper.