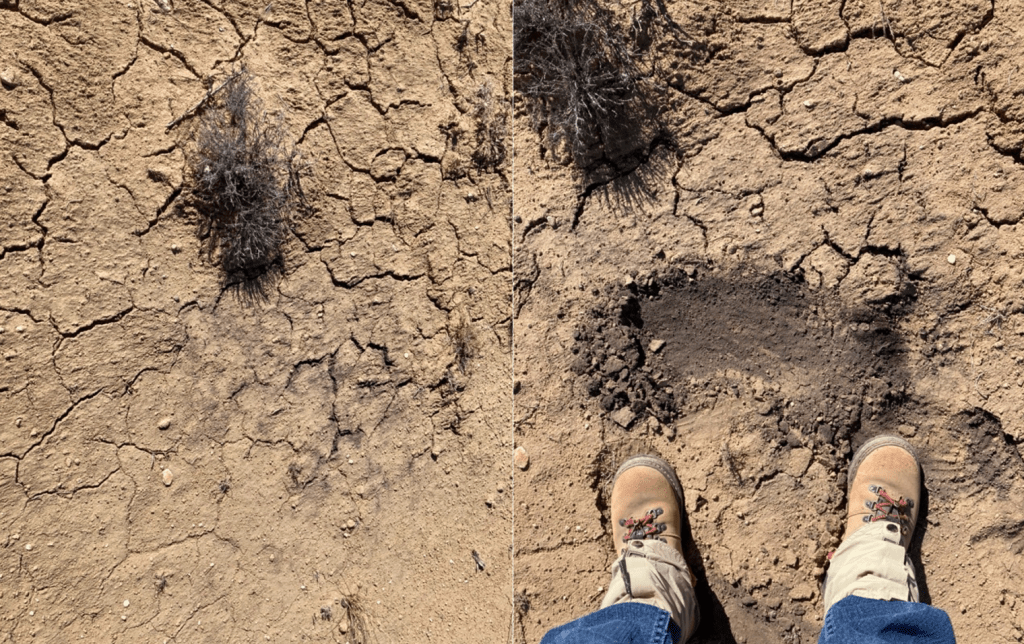

The square-cornered foundation and a couple of scattered sherds say Ancestral Pueblo, but both the vertical orientation and the size of the stones are unusual and impressive. Walls and roof–jacal style, the Southwest version of wattle-and-daub–have long since dissolved into the desert clay.

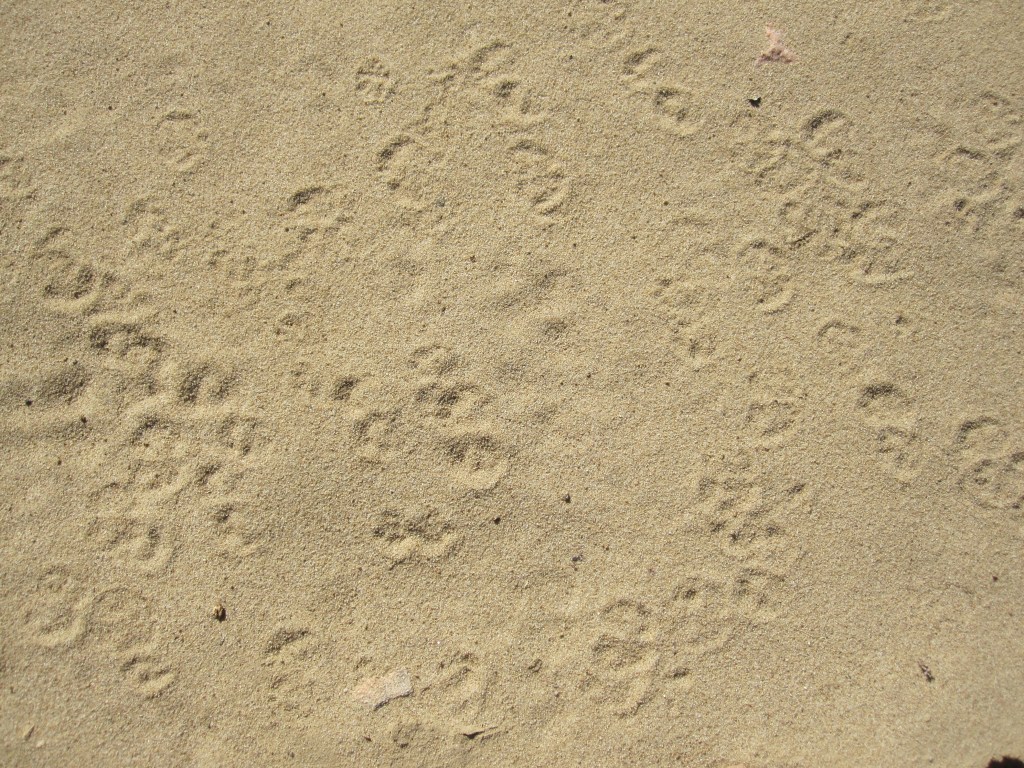

And another house. I have no idea whose, but the excavator left their claw marks above the doorway.